When we think about photographs, our attention is usually drawn to the image itself, overlooking the photograph as a physical object. Yet, the frame, mounting materials, and even the back of a photograph holds valuable context and history. These often-overlooked details can offer vital clues about the people and stories captured within the image, enriching our understanding in ways we might not expect.

At the SJPA, we hold a vibrant collection of physical photographs in all shapes and sizes. From fascinating 19th-century photographic processes to large-scale 6ft tall aerial maps made up of hundreds of collaged images, our collection offers a fascinating visual journey through Jersey’s history.

Within the SJPA collection, we are privileged to hold a selection of various daguerreotypes, which are considered one of, if not the earliest, photographic process, dating back to the late 1830s. This text will explore what a daguerreotype is, before then looking at an intriguing example of one of these treasured artefacts that exists within our collection.

HISTORY OF THE DAGUERREOTYPE

Dating back to its invention in 1839 by French scientist and pioneering photographer Louis Daguerre, the daguerreotype is widely considered to be the first publicly available photographic process. A daguerreotype is made from a silver coated cooper plate which is then, sensitised, exposed, developed, and fixed using various chemicals.

Despite notable competition only two years into its invention by a revolutionary paper based photographic process the calotype, by British scientist William Henry Fox Talbot, the process of daguerreotypes nevertheless remained a commercially viable and popular photographic process throughout the 1840s and 1850s. Due to the exceptional sharpness and image quality daguerreotypes produced, far outperforming the calotype and other similar emerging processes, the daguerreotype remained a go to option for those in the period seeking image quality above all else.

Despite remaining popular for the next 15-20 years, and in spite of developing technologies such as wider lens apertures allowing for ever quicker exposure times, which effectively resolved one of its main criticisms, daguerreotypes were eventually made obsolete by the invention of the glass-based ambrotype (positive collodion) process in the 1850s, resulting in images of a comparative quality at considerably less expense. As a result, there are very little examples of daguerreotypes existing beyond the 1860s.

HOW IS A DAGUERROTYPE MADE?

A daguerreotype is made through a series of 4 different processes:

- Sensitisation – a sheet of silver coated cooper is placed in a box containing iodine for up to an hour, causing sensitisation of the cooper plate.

- Exposure – the cooper plate is then placed into the camera body and exposed to light for anywhere from 3 to 30 minutes, dependent on the size of the lens aperture.

- Developing – the plate is placed in a separate box positioned above a cup of liquid mercury. The mercury is heated, causing vapour to rise and condense onto the plate, resulting in the emergence of a latent image.

- Fixing – the image is then fixed by immersing the plate in either a solution of sea salt or sodium thiosulfate, before then being washed in warm distilled water.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DAGUERROTYPE

Daguerreotypes have unique physical qualities and appearances which can distinguish them from other photographic processes. As a daguerreotype emerges through exposing the image directly onto the plate, each image made is entirely unique and impossible to reproduce onto another surface or material.

Daguerreotypes on the most part are relatively small, typically around 50x80mm. Despite their sizes, the copper base makes daguerreotypes naturally very heavy and weighted. The copper base also means that daguerreotypes are extremely vulnerable. As a result, most are protected by being placed in either glass covering and/or folding frames. Even with this protective casing, daguerreotypes remain extremely fragile and susceptible to physical damage.

One of the most interesting characteristics of daguerreotypes is their unique mirror-like sheen created by their silver coated surface. As a result, daguerreotypes must be held away from light to see the positive image. Conversely, when light reflects against the surface of the image, the image will instead show a negative image, a unique phenomenon which helps make daguerreotypes distinguishable from other otherwise similar looking photographic processes.

EXAMPLE OF A DAUGUERROTYPE IN THE SJPA COLLECTION

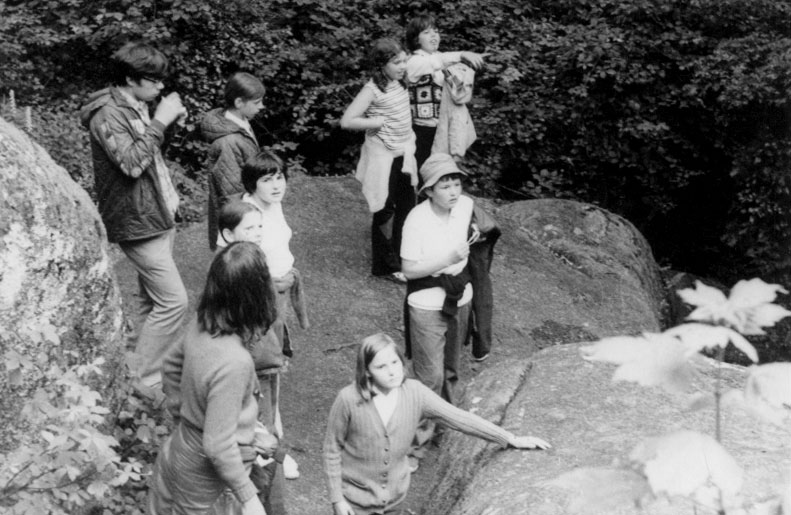

When searching through the daguerreotypes within the SJPA collection, I was immediately drawn to the example below, reference SJPA/036283. This striking example of a daguerreotype is enclosed in a gold-coloured frame underneath a sheet of protective glass, with the edges of the frame containing an elegant and decoratively carved leaf pattern.

SJPA/036283. Portrait of Anne Le Couteur and her daughter Harriet Elizabeth Le Sueur. Process: daguerreotype. Dimensions: 240x160mm. Date: c. 1850s. Photographer: unknown.

The image itself depicts a traditional studio styled portrait of two woman. The individuals in the photograph, identified by the text on the back, are two Jersey residents: Mrs Anne Le Couteur and her daughter, Mrs Harriet Elizabeth Le Sueur. The text also reveals that Anne Le Couteur was the second daughter of the Rector of St Lawrence, Reverend George Du Haume, and that Harriet Elizabeth was known as ‘Mrs Le Sueur of Hamptonne’. Given the photographic process used, along with the fact that Harriet Elizabeth, who passed away at the age of 89 in 1919, appears be a young woman in her early 20s in this image, it would be reasonable to conclude that this photograph was taken at some point in the 1850s. Whilst the photographer and location is unknown, it is likely that the photograph was taken in a studio by a commercial photographer, due to the evident technical quality of the image.

While there is little information available about these two individuals, it’s likely they came from a moderately affluent background. Due to the fact they had a daguerreotype made in the first place, one which for that matter has been enclosed within a beautiful gold-plated frame, implies that they must have paid reasonable amount of money for this item. Additionally, being the daughter and granddaughter of a Parish Rector indicates that the family likely had a respectable standing in society.

Considering the age of this item, combined with the renowned fragility of daguerreotypes, it remains in remarkably good condition. Apart from some slight tarnishing and stains around the edges of the image, likely caused by exposure to airborne contaminants like moisture and dust, and a few minor scratches and scuff marks on the surface, probably from attempts to wipe or clean the plate, the photograph is otherwise in very good condition and well-preserved. During the fixing process of daguerreotypes an additional step was sometimes taken to tone the plate with gold chloride, to provide the item with better protection and durability. I would say in this instance it was very likely that such an action was taken.

When handling the item, it is understandably very heavy. As outlined earlier in this text this is primarily due to copper being a naturally dense metal. Other factors which help to identify the object immediately as a daguerreotype rather than a similar looking tintype for example is, as mentioned earlier, the fact the image shows a negative image when held up to light. In addition, the actual image, not including the frame, measures in at 60x85mm, a very typical size to expect for a daguerreotype.

In summary, this photograph is a fantastic example of an extremely well looked after and preserved daguerreotype. Reflecting on the fact this photograph is likely over 170 years old yet remains an artefact that is very much intact and able to still provide a clear image, is remarkable. This fact serves as an important reminder that photography whilst on one hand provides a visual representation of a subject, physical photographs in themselves remain important and valuable objects which must be appreciated as unique works of art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Coe, B. and Haworth-Booth, M. (1983) ‘Glossary’, in A guide to early photographic practices. Victoria and Albert Museum in association with Hurtwood Press, pp. 17–21.

Starl, T., Fritoz, M. and Harding, C. (1998) ‘A New World of Pictures: The Daguerreotype ’, in A New History of Photography. 2nd edn. Cologne , Germany: Konemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, pp. 33–58.

Images

Photographer, Unknown (undated, c.1850s) Portrait of Anne Le Couteur and her daughter Harriet Elizabeth. Process: daguerreotype. Dimensions: 240x160mm. Société Jersiaise Photographic Archive Collection, SJPA/036283.

Websites

Daniel, M. (2004) Daguerre (1787–1851) and the invention of photography: Essay: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn timeline of art history, The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

Encyclopedia Britannica and Kathleen, K. (2000) Daguerreotype, Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/technology/photography/Daguerreotype (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

Jersey Heritage (undated) Archives and Collections Online, Harriet Elizabeth LE SUEUR died the 4 October age of 89 years buried the 8 October 1919. Minister officiating Rev: Lord Plot 238. Available at: https://catalogue.jerseyheritage.org/collection-search/?si_elastic_detail=archive_110318764 (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

Max Le Feuvre, Assistant Archivist – Societe Jersiaise Photographic Archive